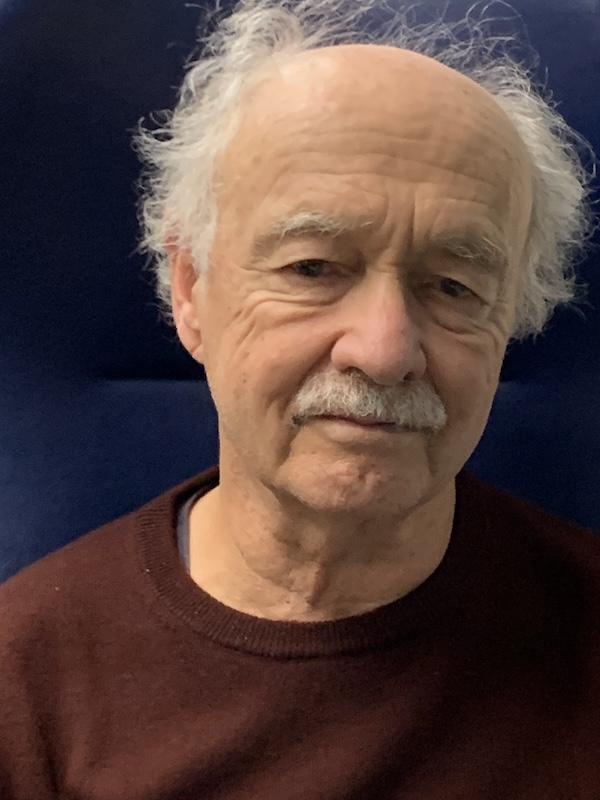

biography

Jim Moore has been writing poetry for more than five decades. His most recent book, Prognosis, was published in 2021 by Graywolf Press. In 2012 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Underground: New & Selected Poems is also available now from Graywolf Press. His new book of poetry, Enter, will be available from Graywolf in May, 2025.

He has won the Minnesota Book Award for his poetry four times. Jim has received grants from the Bush Foundation, the Minnesota State Arts Boards, the Loft Mcknight. His poems have appeared three times in Pushcart Prize Editions as well as in many magazines, including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Nation, The New York Review of Books, American Poetry Review, Harper’s The Kenyon Review, The Threepenny Review, and Water-Stone Review.

Jim lives in Minneapolis and Spoleto, Italy with his wife the photographer JoAnn Verburg. He taught in the Hamline University MFA Program in St. Paul, Minnesota and was often a Visiting Professor at the Colorado College in Colorado Springs, Colorado

‘My Life as a Writer’

Iwas twenty-five in 1968 when I finished graduate school at the University of Iowa (the Writers Workshop) and began teaching nearby at a small junior college in Moline, Illinois. During that first year of teaching (I was barely older than my students), two of the young men dropped out of school and almost immediately were drafted, sent to Vietnam, and killed. I decided, under those circumstances, that I couldn’t continue to accept the teachers’ deferment which was keeping me out of the army. I sent my draft card back to my draft board with a letter saying I couldn’t cooperate with the system any more. In due course, as punishment, I was drafted, refused induction, and was sent to prison where I spent ten months in 1970.

This experience changed everything for me as a writer. I had never lived outside of academic institutions. At first, I hid the fact that I was a poet. Eventually this came out, but instead of finding myself ridiculed, I found myself respected (and far too much) for it. Inmates of all ages, mostly Black and Hispanic, wanted me to teach a poetry class. So I did. I discovered that a big notebook was kept secretly (passed from inmate to inmate so the risk was shared) and at some cost (its discovery would have resulted in the loss of good time, which meant a longer stay in prison) in which inmates kept poems—poems of their own and poems by poets whose work they loved, mostly Black poets, but I remember Neruda was there, Whitman, and Longfellow, of all people.